Sosnoff Theater, Bard College Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

“DMITRIJ”

Opera in four acts, Libretto by Marie Červinková-Riegrová

Music by Antonin Dvořák

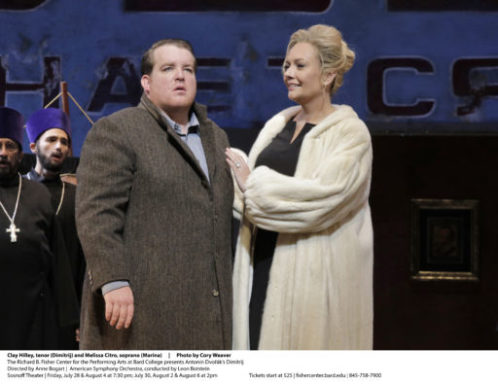

Dmitrij CLAY HILLEY

Marina MELISSA CITRO

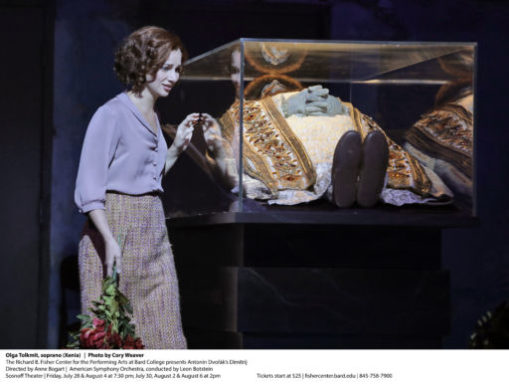

Xenia OLGA TOLKMIT

Marfa NORA SOUROUZIAN

Patriarch Jov PEIXIN CHEN

Prince Shuisky LEVI HERNANDEZ

Basmanov JOSEPH BARRON

Neborsky ROOSEVELT CREDIT

Bucinsky THOMAS McCARGAR

American Symphony Orchestra

Conductor Leon Botstein

Chorus Master James Bagwell

Production Anne Bogart

Set Design David Zinn

Costume Design Constance Hoffman

Lighting Design Brian H. Scott

Language Coach Veronique Firkusny

Annandale-on-Hudson, New York, July 30, 2017

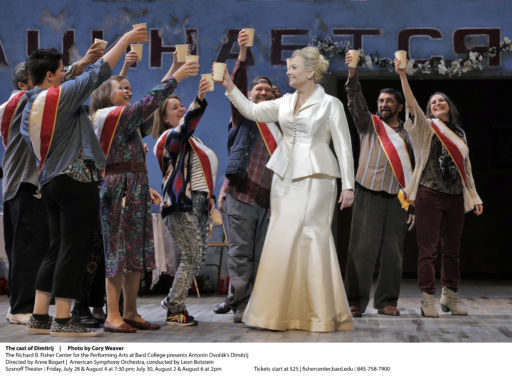

Antonin Dvořák’s Dmitrij was given its fully-staged American debut last week at the Sosnoff Theater, Bard College’s superb Frank Gehry opera house. The opera, a grand opera on the Scribe-Meyerbeer template, had its American concert premiere no longer ago than 1984. It has never been well known outside the Czech lands, in part because no Czech operas other than those that had been translated into German (such as Bartered Bride and Jenufa) got many performances outside the Czech lands until quite lately. Dmitrij is full of massed choral scenes, and though Dvořák was a notable composer of choral music, international choruses rarely study Czech. At the annual Bard SummerScape festival on the cliffside campus about two hours north of New York City, the Bard Festival Chorale sang their Czech ardently and distinctly, Leon Botstein led the American Symphony Orchestra in a surging, lyrical performance, and everyone seemed to express surprise at how beautiful the music was.

Antonin Dvořák’s Dmitrij was given its fully-staged American debut last week at the Sosnoff Theater, Bard College’s superb Frank Gehry opera house. The opera, a grand opera on the Scribe-Meyerbeer template, had its American concert premiere no longer ago than 1984. It has never been well known outside the Czech lands, in part because no Czech operas other than those that had been translated into German (such as Bartered Bride and Jenufa) got many performances outside the Czech lands until quite lately. Dmitrij is full of massed choral scenes, and though Dvořák was a notable composer of choral music, international choruses rarely study Czech. At the annual Bard SummerScape festival on the cliffside campus about two hours north of New York City, the Bard Festival Chorale sang their Czech ardently and distinctly, Leon Botstein led the American Symphony Orchestra in a surging, lyrical performance, and everyone seemed to express surprise at how beautiful the music was.

Dvořák is better known for symphonies, tone poems, Slavonic Dances and chamber music  than for opera, but no one ever questioned his gifts for melody and orchestration. The imperious Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, admired Dmitrij’s premiere in 1882, and a feud between Old Czechs and Young Czechs over whether or not Dvořák had offended Smetana was inadvertent on Dvořák’s part and soon died away from lack of encouragement. The opera was performed some sixty times in Prague before the composer’s death, but never caught on anywhere else. Of course it’s beautiful.

than for opera, but no one ever questioned his gifts for melody and orchestration. The imperious Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, admired Dmitrij’s premiere in 1882, and a feud between Old Czechs and Young Czechs over whether or not Dvořák had offended Smetana was inadvertent on Dvořák’s part and soon died away from lack of encouragement. The opera was performed some sixty times in Prague before the composer’s death, but never caught on anywhere else. Of course it’s beautiful.

But Dmitrij is also slow and static. Four hours of beautiful can sweep you along or they can be ponderous. Dvořák’s librettist was inexperienced, and while the love-triangle-played-out-against-national-uproar plot was tried and true (Aida comes to mind; also Les Huguenots, La Juive and La Favorite), sometimes it does not come alive. Dvořák never seems to know when he’s made his point and it’s time to move on or quite how to build a scene to a brisk climax. I concluded, as at other Dvořák operas I’ve attended (Russalka, Armida, Vanda) that the man did not have the opera gene. Dramatic form was not instinct in him, and he did not seek out hit plays as models for his stage works, as most successful opera composers of the century did.

For Dmitrij, Dvořák chose the story of the pretender to the Muscovite throne upon the deaths of Boris and Fyodor Godunov. He is unlikely to have known Moussorgsky’s opera, premiered in 1873 but not performed in the west until 1908, but his librettist, Marie Červinková-Riegrová, the daughter and granddaughter of Slavic nationalist politicians, may well have read Pushkin’s play, Moussorgky’s source. In Dvořák’s opera, Dmitrij’s Polish bride, Marina, refuses to accept Russian “ways,” taunts Dmitrij to a mazurka rhythm, and invents a tale of mixed and murdered babies right out of Il Trovatore. Dmitrij then falls in love with Xenia Godunova, Boris’s hapless daughter, whom he has rescued from assault. Dmitrij’s mother, Marfa, who had “recognized” him in Act I, changes her mind in Act IV, in a scene borrowed from Le Prophète. (There is also a conspirators’ chorus into which, as in Ernani, the objective, Dmitrij, intrudes. Červinková-Riegrová seems to have been desperate to try anything that had worked for someone else.) Xenia is murdered by Marina in a jealous fit, and Prince Shuisky, leader of the Russian rebels, murders Dmitrij who has earlier spared Shuisky’s life. None of these pile-on incidents seems sufficiently motivated by the story and all of them linger, musically, longer than they have to. This is a beautiful but bloated opera, wonderful in festival circumstances but not a candidate for the repertory.

At SummerScape, it did not help things that Anne Bogart, the director, refused to set the piece anywhere near 1606 or the Kremlin, site of Dmitrij’s coronation and murder. My guess is they couldn’t afford fancy costumes for anyone but the Orthodox priests. Bogart says the confusion of the Time of Troubles (1598-1613) reminded her of the confusion in 1989 at the fall of communism, which I suppose means she regards Putin as a Romanov. (There was a golden-haired child dancing through the set at odd times, representing the future—Michael Romanov, I’d imagine.) The single set was a battered, unkempt gymnasium-assembly room in a post-Stalin Era public building (no outdoors! No Kremlin towers in the distance!) and the costumes were drab and casual except for the posh gowns of Marina and Marfa. Xenia has no princess clothes but only rags (and flat shoes). Soldiers get to carry AK-47s. Gangs of assassins have flashlights wavering in the dark, which is getting to be a cliché but remains effective. Crowd movement (and there’s a lot of it) was not among Bogart’s stronger foci. The static nature of this opera was emphasized at every turn. Compared to this Dmitrij, Verdi’s Vespri Siciliani is a tight, clear, active story. In my own despite, however, it is only fair to say that a glance about the Sosnoff Theater during the final act—will Marfa swear Dmitrij is Dmitrij or will she go back on her earlier recognition?—showed the audience at every level sitting up straight, attention caught, eager to find out how the tale would come out.

At SummerScape, it did not help things that Anne Bogart, the director, refused to set the piece anywhere near 1606 or the Kremlin, site of Dmitrij’s coronation and murder. My guess is they couldn’t afford fancy costumes for anyone but the Orthodox priests. Bogart says the confusion of the Time of Troubles (1598-1613) reminded her of the confusion in 1989 at the fall of communism, which I suppose means she regards Putin as a Romanov. (There was a golden-haired child dancing through the set at odd times, representing the future—Michael Romanov, I’d imagine.) The single set was a battered, unkempt gymnasium-assembly room in a post-Stalin Era public building (no outdoors! No Kremlin towers in the distance!) and the costumes were drab and casual except for the posh gowns of Marina and Marfa. Xenia has no princess clothes but only rags (and flat shoes). Soldiers get to carry AK-47s. Gangs of assassins have flashlights wavering in the dark, which is getting to be a cliché but remains effective. Crowd movement (and there’s a lot of it) was not among Bogart’s stronger foci. The static nature of this opera was emphasized at every turn. Compared to this Dmitrij, Verdi’s Vespri Siciliani is a tight, clear, active story. In my own despite, however, it is only fair to say that a glance about the Sosnoff Theater during the final act—will Marfa swear Dmitrij is Dmitrij or will she go back on her earlier recognition?—showed the audience at every level sitting up straight, attention caught, eager to find out how the tale would come out.

Following the Wagnerian style then chic (1882 is the year of Parsifal), the score is not divided into discreet numbers but flows from one to the next, constructed on motives based on each character or theme. As usual with SummerScape’s revivals of important but neglected operas (in fifteen years, they have staged such works as Taneyev’s Oresteia, Schumann’s Genoveva, Schreker’s Die Ferne Klang and Smyth’s The Wreckers—Rubinstein’s Demon is slated for next year), the youthful singers were always decent and often remarkable.

The title role is long and stentorian: Dmitrij must declaim, fight, woo and defy crowds, woo and defy ladies, and die heroically. Clay Hilley, who has sung Siegfried and Radames, did an extraordinary job last Sunday, swiftly attaining the proper level of passion and never pulling back from it. As sheer vocal athleticism, it was an astonishing performance but there wasn’t much subtlety about it, much gradation to suit emotional waywardness, and he hardly seemed to be paying attention at all during Marina’s tirade and revelation of his birth. Melissa Citro, tall and blonde and fierce, sang Marina, a termagant role that must race through hoops of music. Shrill and of wandering pitch in Act II, she later pulled herself together for many effective dramatic phrases effectively grounded. The contrast with her rival, Xenia Godunova, could hardly have been more striking: Not only does Xenia have gentler music to sing, but Olga Tolkmit, a slight figure in drab clothes, has far less of a stage-eating presence. She has a nice rounded soprano, however, that builds to climaxes (as when Marina has her stabbed), and I’m not sure how much of her hiding in the shadows, wandering aimlessly on and off, was director Bogart’s idea. The most striking female voice on stage belonged to Nora Sourouzian as Marfa, Dmitrij’s long-lost mother. Sourouzian seemed unusually well dressed and radiant for a self-effacing nun, but her voice was sumptuous and stirring. Among the smaller male roles, Peixin Chen had the ponderous authority for the patriarch and Joseph Barron was effective in the angry, bitten-off phrases of the brutal Basmanov. The crowd around me buzzed happily at the unexpected charm of the score, but the slightness of the drama makes its inclusion in the international repertory seem unlikely. It was a pleasure but not a thrill. Photo Cory Weaver

defy ladies, and die heroically. Clay Hilley, who has sung Siegfried and Radames, did an extraordinary job last Sunday, swiftly attaining the proper level of passion and never pulling back from it. As sheer vocal athleticism, it was an astonishing performance but there wasn’t much subtlety about it, much gradation to suit emotional waywardness, and he hardly seemed to be paying attention at all during Marina’s tirade and revelation of his birth. Melissa Citro, tall and blonde and fierce, sang Marina, a termagant role that must race through hoops of music. Shrill and of wandering pitch in Act II, she later pulled herself together for many effective dramatic phrases effectively grounded. The contrast with her rival, Xenia Godunova, could hardly have been more striking: Not only does Xenia have gentler music to sing, but Olga Tolkmit, a slight figure in drab clothes, has far less of a stage-eating presence. She has a nice rounded soprano, however, that builds to climaxes (as when Marina has her stabbed), and I’m not sure how much of her hiding in the shadows, wandering aimlessly on and off, was director Bogart’s idea. The most striking female voice on stage belonged to Nora Sourouzian as Marfa, Dmitrij’s long-lost mother. Sourouzian seemed unusually well dressed and radiant for a self-effacing nun, but her voice was sumptuous and stirring. Among the smaller male roles, Peixin Chen had the ponderous authority for the patriarch and Joseph Barron was effective in the angry, bitten-off phrases of the brutal Basmanov. The crowd around me buzzed happily at the unexpected charm of the score, but the slightness of the drama makes its inclusion in the international repertory seem unlikely. It was a pleasure but not a thrill. Photo Cory Weaver