New York, Metropolitan Opera, Season 2018/2019

“IOLANTA”

Opera in one act, libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, based on the play King René’s Daughter by Henrik Hertz.

Music by Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky

King René VITALIJ KOWALJOW

Iolanta SONYA YONCHEVA

Duke Robert of Burgundy ALEXEY MARKOV

Count Gottfried Vaudémont ALEXEY DOLGOV

Ibn-Hakia ELCHIN AZIZOV

Martha LARISSA DIADKOVA

Brigitta ASHLEY EMERSON

Laura MEGAN MARINO

Bertrand HAROLD WILSON

Alméric MARK SCHOWALTER

“BLUEBEARD’S CASTLE”

Opera in one act, libretto by Béla Balázs, based on the fairy tale by Charles Perrault.

Music by Béla Bartók

Judith ANGELA DENOKE

Duke Bluebeard GERALD FINLEY

Chorus and Orchestra of the Metropolitan Opera

Conductor Henrik Nánási,

Production Mariusz Trełinski

Set Designer Boris Kudlička

Costume Designer Marek Adamski

Lighting Designer Marc Heinz

Projection Designer Bartek Macias

Choreographer Tomasz Jan Wygoda

Co-production of the Metropolitan Opera and Teatr Wielki-Polish National Opera.

New York, 24 January, 2019

Béla Bartók’s only opera, Bluebeard’s Castle, premiered in 1918 shortly before the end of World War I at what was still called the Royal Opera House in Budapest. The piece was not a hit. During the composer’s lifetime (he died in New York in 1945), there was one revival in Budapest (in 1936) and three other productions, two in German (in Frankfurt and Berlin) and one in Italian (Florence). Bartók was not, therefore, inspired to work again in the operatic form. The opera’s transformation from obscurity to ubiquity, to its present position among the most beloved of twentieth-century scores has been an astonishment. The small cast (two singers, no chorus) and the static drama make it a favorite for orchestral performance, as does the work’s brevity. These things also make it a popular choice for adventurous stage directors, but in the opera house it is a bit short for a full evening, and there is no obvious choice for a pairing. At the Met, it was first paired (in 1974, in English) with Gianni Schicchi. Later this was changed for Schönberg’s Erwartung, both works given in their original tongues. Erwartung also moves through a symbolic, dreamlike narrative.

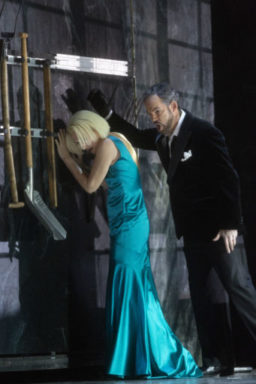

Currently, the Met pairs the opera with Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta, like Bluebeard a one-act opera with a fable-like story set in fifteenth-century France—insofar as either work is set in any particular time or place. They have little else—musically, very little indeed—in common. Iolanta, Tchaikovky’s last opera, is a number-opera, old-fashioned for its era, with little of the mood-painting or psychological underpinning of his previous drama, The Queen of Spades. Iolanta tells of a blind princess who can only be cured if she learns there is a sense, sight, that she does not possess—a fact her father, the saturnine King René, has concealed from her since birth, allowing none of her servants to mention things like color or distant views. But a stranger comes, falls in love, and asks her for a red rose—but she keeps giving him white ones. The secret is out! In the expressionistic, tonally uneasy Bluebeard, the lovely young bride insists (on the very first night!) on learning every secret of her glum and taciturn husband. She defies the rumors—but she’s heard them all right—that he’s murdered his previous wives, and she ignores his warnings to leave certain doors unopened. In the Mariusz Trełinski staging of this quirky double bill now revived at the Met, Iolanta’s charming flower garden is a cell in a dismal swamp full of uprooted trees and half-seen beasts. Everything is black or white or shades of brown—except the red roses and Iolanta’s blue dress. Even the two invading knights wear white ski togs. As for Bluebeard’s Castle, in the mated production, the uprooted trees return, but they seem to surround an elevator shaft that descends ever deeper, symbolically, into an inner consciousness. The only color is Judith’s green dress. Trełinski seems to wish to make a connection between the overprotective father, King René, and the unquestioning faith of his naïve daughter—until dawning love stirs her curiosity—and the morbid Bluebeard, who (we discover) keeps his brides (dead or undead?) in the seventh and innermost of his dungeons. The question about the outer world that liberates Iolanta is the question about his inner world that imprisons Judith. Love conquers nothing here. Solitude reigns.

Currently, the Met pairs the opera with Tchaikovsky’s Iolanta, like Bluebeard a one-act opera with a fable-like story set in fifteenth-century France—insofar as either work is set in any particular time or place. They have little else—musically, very little indeed—in common. Iolanta, Tchaikovky’s last opera, is a number-opera, old-fashioned for its era, with little of the mood-painting or psychological underpinning of his previous drama, The Queen of Spades. Iolanta tells of a blind princess who can only be cured if she learns there is a sense, sight, that she does not possess—a fact her father, the saturnine King René, has concealed from her since birth, allowing none of her servants to mention things like color or distant views. But a stranger comes, falls in love, and asks her for a red rose—but she keeps giving him white ones. The secret is out! In the expressionistic, tonally uneasy Bluebeard, the lovely young bride insists (on the very first night!) on learning every secret of her glum and taciturn husband. She defies the rumors—but she’s heard them all right—that he’s murdered his previous wives, and she ignores his warnings to leave certain doors unopened. In the Mariusz Trełinski staging of this quirky double bill now revived at the Met, Iolanta’s charming flower garden is a cell in a dismal swamp full of uprooted trees and half-seen beasts. Everything is black or white or shades of brown—except the red roses and Iolanta’s blue dress. Even the two invading knights wear white ski togs. As for Bluebeard’s Castle, in the mated production, the uprooted trees return, but they seem to surround an elevator shaft that descends ever deeper, symbolically, into an inner consciousness. The only color is Judith’s green dress. Trełinski seems to wish to make a connection between the overprotective father, King René, and the unquestioning faith of his naïve daughter—until dawning love stirs her curiosity—and the morbid Bluebeard, who (we discover) keeps his brides (dead or undead?) in the seventh and innermost of his dungeons. The question about the outer world that liberates Iolanta is the question about his inner world that imprisons Judith. Love conquers nothing here. Solitude reigns.

The Met has put a luxurious cast into these works, as it often does with modern works like The Rake’s  Progress and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk whose appeal to their conservative audience can be doubted. Sonya Yoncheva sings Iolanta with a lovely flowing line and more hesitation, more nervous expresoin than the brash Anna Netrebko gave the role when the production premiered in 2015. Yoncheva seemed touchingly desperate at times, which suited the gloom of the set. I had been looking forward to Matthew Polenzani’s Vaudémont, but on opening night he was indisposed, replaced by a young Russian tenor, Alexey Dolgov, who made a most appealing, ardent impression. Vitalij Kowaljow, whose dark, sinister bass, an instrument of restrained power and great character in the Bulgarian tradition of Ghiaurov and Christoff, has been waiting in the wings for too many years, in my opinion, for the proper showcase role. He’s always interesting, internal, implying as much as his rich instrument declares, and his René drew attention to this underwritten role and his brooding presence in his daughter’s imprisonment. Alexey Markov, who possesses a very agreeable baritone sound, sang the rather pointless role of Duke Robert most agreeably—but do we need an aria from this character, and right when the climax is upon us? Harold Wilson and the great Larissa Diadkova undertook the small parts of the woodcutter and his wife who care for Iolanta with the proper style. Henrik Nánási, making his house debut, led a sure and logical progression of the moody melodies and soothing underscoring of Tchaikovsky’s score. But I suspect that, like us, he was holding himself back for the evening’s pièce résistance.

Progress and Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk whose appeal to their conservative audience can be doubted. Sonya Yoncheva sings Iolanta with a lovely flowing line and more hesitation, more nervous expresoin than the brash Anna Netrebko gave the role when the production premiered in 2015. Yoncheva seemed touchingly desperate at times, which suited the gloom of the set. I had been looking forward to Matthew Polenzani’s Vaudémont, but on opening night he was indisposed, replaced by a young Russian tenor, Alexey Dolgov, who made a most appealing, ardent impression. Vitalij Kowaljow, whose dark, sinister bass, an instrument of restrained power and great character in the Bulgarian tradition of Ghiaurov and Christoff, has been waiting in the wings for too many years, in my opinion, for the proper showcase role. He’s always interesting, internal, implying as much as his rich instrument declares, and his René drew attention to this underwritten role and his brooding presence in his daughter’s imprisonment. Alexey Markov, who possesses a very agreeable baritone sound, sang the rather pointless role of Duke Robert most agreeably—but do we need an aria from this character, and right when the climax is upon us? Harold Wilson and the great Larissa Diadkova undertook the small parts of the woodcutter and his wife who care for Iolanta with the proper style. Henrik Nánási, making his house debut, led a sure and logical progression of the moody melodies and soothing underscoring of Tchaikovsky’s score. But I suspect that, like us, he was holding himself back for the evening’s pièce résistance.

Angela Denoke, a singing actress of international remark, is better known in New York as a lieder artist than an opera star—she made her Met debut last year as the Marschallin. Her tall, slim Judith resembled one of the uprooted trees surrounding the impressionistic castle into which set designer Boris Kudlička had transformed Iolanta’s forest cell. Her voice swells in an ardent if chalky, Germanic voluptuosness as Judith’s love for her unknown, unknowable spouse battles with ever rising, choking terror. She implied this terror with little gestures, kept to herself so that he should not see them—but he did—and so did we. This is an opera of repressed panic. It was therefore a bit disappointing that her one moment of release, the spectacular high C upon the opening of the Fifth Door, was not in her arsenal, at least on the first night. The orchestra—and here Maestro Nánási and the Met Orchestra allowed themselves to blaze out as if this were not a tale of hidden personalities in hidden conflict. The orchestra tossed through the scores intricacies like a happy stallion at play, free at last, delighting in every sonority. The Bluebeard on this occasion was another of the world’s great singing actors, Gerard Finley, who is even taller and more brooding a presence than Denoke’s Judith.

Angela Denoke, a singing actress of international remark, is better known in New York as a lieder artist than an opera star—she made her Met debut last year as the Marschallin. Her tall, slim Judith resembled one of the uprooted trees surrounding the impressionistic castle into which set designer Boris Kudlička had transformed Iolanta’s forest cell. Her voice swells in an ardent if chalky, Germanic voluptuosness as Judith’s love for her unknown, unknowable spouse battles with ever rising, choking terror. She implied this terror with little gestures, kept to herself so that he should not see them—but he did—and so did we. This is an opera of repressed panic. It was therefore a bit disappointing that her one moment of release, the spectacular high C upon the opening of the Fifth Door, was not in her arsenal, at least on the first night. The orchestra—and here Maestro Nánási and the Met Orchestra allowed themselves to blaze out as if this were not a tale of hidden personalities in hidden conflict. The orchestra tossed through the scores intricacies like a happy stallion at play, free at last, delighting in every sonority. The Bluebeard on this occasion was another of the world’s great singing actors, Gerard Finley, who is even taller and more brooding a presence than Denoke’s Judith. Whenever I have heard Mr. Finley at the Met, the enormous house has seemed a size too large for him—as it is for many British singers—but he never makes the mistake of oversinging or bluster to compensate. Bluebeard, so private yet so overwhelming, so likely to swallow a bride when he opens his mouth as to produce a sound, is clearly a role that means a lot to him, one that he intends to mean a great deal to us. His quietness on this occasion seemed an acting choice, a restraint. He did not threaten Judith with vocal power but with stern gesture and hauteur. He seemed to be dreaming the later scenes, as if depicting his inner world and the place Judith, his fantasy now and not a real woman, would play in his sanctum henceforward. This was luxury casting in many ways—louder Bluebeards and higher Judiths have made glorious impressions (as I say, the opera gets done a lot, and done well—the New York Philharmonic is doing it next year, paired with Erwartung), but here the weird Trełinski production came into its own. One might have wished to hear the singers in a smaller room—that is the only thing one would have changed. Photo Marty Sohl / Met Opera

Whenever I have heard Mr. Finley at the Met, the enormous house has seemed a size too large for him—as it is for many British singers—but he never makes the mistake of oversinging or bluster to compensate. Bluebeard, so private yet so overwhelming, so likely to swallow a bride when he opens his mouth as to produce a sound, is clearly a role that means a lot to him, one that he intends to mean a great deal to us. His quietness on this occasion seemed an acting choice, a restraint. He did not threaten Judith with vocal power but with stern gesture and hauteur. He seemed to be dreaming the later scenes, as if depicting his inner world and the place Judith, his fantasy now and not a real woman, would play in his sanctum henceforward. This was luxury casting in many ways—louder Bluebeards and higher Judiths have made glorious impressions (as I say, the opera gets done a lot, and done well—the New York Philharmonic is doing it next year, paired with Erwartung), but here the weird Trełinski production came into its own. One might have wished to hear the singers in a smaller room—that is the only thing one would have changed. Photo Marty Sohl / Met Opera

New York, Metropolitan Opera: “Iolanta” & “Bluebeard’s Castle”