Sydney. Joan Sutherland Theatre, Sydney Opera House. 2017 Season.

“KING ROGER”(KROL ROGER)

Opera in 3 acts. Libretto by Jarosław Iwaszkiewicz and the composer

Music by Karol Szymanowski

Sung in Polish with English surtitles

King Roger ll of Sicily MICHAEL HONEYMAN

Archbishop GENNADY DUBINSKY

Deaconess DOMINICA MATTHEWS

Roxana LORINA GORE

Edrisi JAMES EGGLESTONE

Shepherd SAIMIR PIRGU

Opera Australia Orchestra and Chorus

Conductor Andrea Molino

Chorus Master Anthony Hunt

Sydney Children’s Choir

Chorus Master Lyn Williams

Director Kasper Holten Revival Director Amy Lane

Designer Steffen Aarfing

Lighting Designer Jon Clark

Video Designer Luke Halls

Choreographer Cathy Marston

Fight Director Nigel Poulton

Co-production with the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and Dallas Opera

Sydney. 20th January, 2017.

The Australian Opera is not new to impressive and original productions. In fact it could be said to be its trademark, all the more noteworthy given the unsurmountable limitation of its small stage and pit. So it was no surprise to see the widely acclaimed co-production with the Royal Opera House Covent Garden and Dallas Opera, of the rarely performed opera in Polish of King Roger (Krol Roger) by Karol Szymanowski at the Sydney Opera House.

Szymanowski was fascinated by Oriental and ancient Greek culture and spent much time in Sicily and North Africa. He was known to have a devoted predilection for the mystic and lyrical poetry of the Persian poet Hafiz, whose ghazals speak of wine and love, presenting the ecstasy and freedom from restraint as well as targeting religious hypocrisy.

Although Symanowski’s eponymous hero bears very little resemblance to what we know of the historical Norman Sicilian King Roger, the historical context and situation of King Roger as a figure who straddled east and west between The Holy Roman, the Byzantium Empire and his majority Arab speaking and Muslim capital city Palermo, where a substantial Greek population also resided, provided Szymanowski with elements that could establish a background that would lend itself to the themes he wished to express. While Roger cleverly blended Islamic, Greek and Byzantine culture into his administration, and undertook a program of administrative reform and architectural commissions that brought out all that was best of these cultures, his hybridity is apparent in the depictions of him in Siculo -Norman art. His portrayals in the Palatine Chapel are both of a Byzantine Emperor and a Muslim Caliph. It has been suggested that this work, mirrors Szymanowski’s own inner struggles and search for identity. The story deals with the arrival to the kingdom of a man who calls himself the Shepherd, and who is teaching a new strange faith which go against Roger’s tenets but which attract his wife and people. In his stage instructions to the first two acts, Szymanowski gives a detailed description of the historical locations of Palermo, the Byzantine Palatine Chapel and the palace courtyard, and of the antique ruins of the Sicilian landscape in the third. The three short acts are often referred to as the Byzantine, the Oriental and the Hellenic and are also characterised by distinct musical styles. However, Kasper Holten‘s arresting staging (revived by Amy Lane) and Steffens Aarfing‘s stunningly monumental set design, shift the emphasis from the geographical location to a psychological world to highlight what Kasper Holten has described as the theme of the work, ‘that of identity; the perennial battle between mind and body, duty and desire.’ The outward struggle is between ideologies represented by the Church and the shepherd,who represents pagan principles; the struggle between sacred and profane love. The inward struggle, however, is that between the King’s psyche and soul. The composer himself described the work, not as an opera but variously as a ‘misterium’, musical drama, Sicilian drama and spectacle. In fact there is very little action and no real interaction between the characters.

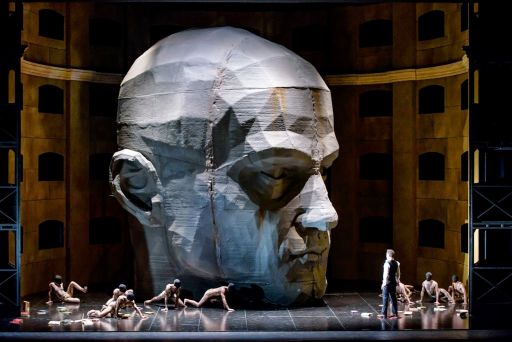

Aarfing’s gargantuan, rough-hewn, stone-like head sculpture, reminiscent of the bronze colossus head of the emperor Constantine, that fills the stage, is awe inspiring and imposes the grandeur and solidity of the established order. An amphitheatre structure encircles the extremities of the stage, the chorus appearing in its a arches as if in a matroneo of the cathedral in the first act, with fleeting visions of Roxana and the Shepherd in the third. The lighting and video designers Jon Clark and Luke Halls create a breathtaking range of effects which sweep over the colossus changing its forms and expressions to accompany the musical and dramatic content.

The second act is played inside the head, lined with books in its upper reaches, writhing figures on its ground level and a series of contorted stairs linking the various platforms, over which the characters move, slither and jump, underscoring the tortuous meanderings of the mind and heart. The costumes have been updated from antiquity to the early 1930’s, around the time the opera was written. There were other 1930 touches; the book burning was one.

The scoring is lush and evocative with a colouristic sensitivity to the sounds of the impressionists. The orchestra played beautifully under the commanding direction of Andrea Molino who conducted by memory. The solo instruments throughout added moments of grace, sensuality and refinement. The audience was captivated from the opening bars with the muted sound of the gong and the haunting a cappella choirs weaving their Byzantine chorale. The children’s choir was perfect. Firm, clear, pure tones floated easily and effortlessly. They got a deserving round of applause after the first act. From the nobility of their chorale the adult chorus deftly transformed into an angry crowd without losing their vocal control and precision.

Michael Honeyman‘s performance as King Roger gained in stature as the evening progressed. At the beginning his character betrayed a sense of uncertainty which made his temptation seem less dramatic. Lorina Gore as Roxana enchanted with the expressiveness of the one extractable aria of the work, Roxana’s Lullaby. Her voice was lustrous and relaxed in the mellifluous Eastern melismas, consistently maintaining a poise of her own. As it should be, the tenor Saimir Pirgu shone in his role as the shepherd. His voice bright and clear but sweet and even, especially noteworthy in the high tenor register of his seductive song ‘My god is as beautiful as I….’ His character came across as the most convincing of the three, but then again it is also the most straightforward.

James Egglestone was a fine Edrisi. He made the role incisive, vocally and theatrically, without overstepping his character as a courtier. Gennaro Dubinsky was an authoritative presence as the Archbishop and Dominica Matthews a strong Deaconess. Under the imaginative direction of the choreographer Cathy Marston 10 solo dancers who represented the instinctive desires and longings of King Roger provided a well honed and calibrated physicality to the staging. The final scene was impressively sung and acted by Michael Honeyman, although many in the audience seemed confused about the ending finding it unresolved and ambiguous. In any case, the opening night was received enthusiastically by the audience with their thunderous applause for the many curtain calls.

Sydney Opera House: “King Roger” (Krol Roger)