Berlino, Komische Oper – Stagione Lirica 2011/2012

“DIE SIEBEN TODSUNDEN” (I sette peccati capitali)

Balletto con canto in sette parti su libretto di Bertold Brecht

Musica di Kurt Weill

Anna DAGMAR MANZEL

Vater JOSKA LEHTINEN

Bruder ADAM CIOFFARI

Bruder MANUEL GUNTHER

Mutter TIM KLASKI

Orchestra della Komische Oper Berlin

Direttore Kristiina Poska

Pianoforte Frank Schulte

Regia Barrie Kosky

Coreografia Otto Pichler

Drammaturgia Bettina Auer

Berlino, 12 febbraio 2012

If the Komische Oper’s production of Weill/Brecht’s 1933 Ballet Chanté proves anything, it is that sins of omission are not deadly, and that sins of addition are only slightly irritating if done well. Following up on the successful collaboration of Director Barrie Kosky, and actress/singer Dagmar Manzel in Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate the Komische Oper apparently decided to produce Die sieben Todsünden as a one-woman show, with a few piano cabaret songs thrown in before and after the actual title piece.

If the Komische Oper’s production of Weill/Brecht’s 1933 Ballet Chanté proves anything, it is that sins of omission are not deadly, and that sins of addition are only slightly irritating if done well. Following up on the successful collaboration of Director Barrie Kosky, and actress/singer Dagmar Manzel in Cole Porter’s Kiss Me, Kate the Komische Oper apparently decided to produce Die sieben Todsünden as a one-woman show, with a few piano cabaret songs thrown in before and after the actual title piece.

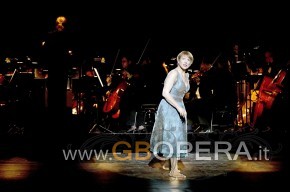

It was a good one-woman show. Ms. Manzel carried it off with an energetic and varied performance style and a voice of many colors and wide range. She succeeds as both a cabaret singer and a stage performer and certainly makes a good evening out of it, but the program does list this as a “Ballett mit Gesang von Kurt Weill”, so one must ask: what Ballett?

The orchestra was at the back of the stage and played Weill’s music beautifully and movingly under the  graceful direction of Kritijana Poska. The male quartet was divided in Loges on either side of the stage which occasionally led to small coordination and intonation problems. Other than a gauzy black curtain which Ms. Manzel opened and closed a few times and a light which descended at the beginning (Berlin im Licht?) the stage was bare and Manzel carried the whole performance.

graceful direction of Kritijana Poska. The male quartet was divided in Loges on either side of the stage which occasionally led to small coordination and intonation problems. Other than a gauzy black curtain which Ms. Manzel opened and closed a few times and a light which descended at the beginning (Berlin im Licht?) the stage was bare and Manzel carried the whole performance.

Originally commissioned as part of the short lived but influential Les Ballets 1933 and involving Georges Balanchine as choreographer, as well as another Ballet Russe veteren as co-sponsor, this piece was written for ballerina Tilly Losch and Lotte Lenya, apparently look alikes, and wives of the rich American patron of Surrealists Edward James, and Weill, respectively. Whatever the reasons for having a singer and a dancer portray two aspects of the same character, the influence of dance has an intrinsic and palpable impact on the piece. As valiantly as she tried with strenuous theatrical gestures and effective use of spotlighting, Ms. Manzel could not fill the gaps. Perhaps most telling was her near success in a piece clearly intended to be danced and accompanied by the male quartet.  Ms. Manzel turned in circles for what seemed an eternity-how she managed was in itself a wonder-and when she suddenly stopped the audience applauded. The physical tension and release-an essential element of dance-gave this music the life which was so sorely missed in many places.

Ms. Manzel turned in circles for what seemed an eternity-how she managed was in itself a wonder-and when she suddenly stopped the audience applauded. The physical tension and release-an essential element of dance-gave this music the life which was so sorely missed in many places.

The performance started with Ms. Manzel and pianist Frank Schulte running through a medley of cabaret and Broadway songs including Surabaya Johnny, and alternating sentimental Weill with the edgier pieces with Brecht’s lyrics. Not a bad beginning, and perhaps a way to extend a short performance to over an hour and a half. A single piano accompanied song was added after the moving conclusion of Die sieben Todsünden, maybe for symmetry or as a Brechtian gesture. It was a mistake, but not a deadly one. While the evening was entertaining it was not nearly sinful enough.