Milan. Teatro alla Scala. Opera and Ballet Season 2016/17.

“DON CARLO”

Opera in 5 acts- based on Friedrich Schiller’s play Don Carlos, libretto by François-Joseph Méry and Camille Du Locle. Translated into Italian by Achille De Lauzières and Angelo Zanardini.

Music by Giuseppe Verdi

Philip ll, King of Spain FERRUCCIO FURLANETTO

Don Carlo, Infante of Spain FRANCESCO MELI

Rodrigo, Marchis of Posa SIMONE PIAZZOLA

Grand Inquisitor MIKA KARES

A Friar MARTIN SUMMER*

Elizabeth de Valois KASSIMIRA STOYANOVA

Princess Eboli EKATERINA SEMENCHUK

Tebaldo, page to Elizabeth TERESA ZISSER

Count Lerma/A Royal Herald AZER ZADA*

A Voice from Heaven CÉLINE MELLON*

Flemish Deputies GUSTAVO CASTILLO*, ROCCO CAVALLUZZI*, DONGHO KIM*,VICTOR SPORYSHEV, CHEN LINGJIE,**PAOLO INGRASCIOTTA*

*Soloists from the La Scala Opera Academy

**Student of the Milan ‘Giuseppe Verdi’ Conservatorium

Orchestra and Chorus of Teatro alla Scala

Conductor Myung-Whun Chung

Chorus Master Bruno Casoni

Director Peter Stein

Designer Ferdinand Wögerbauer

Costumes Anna Maria Heinreich

Lighting Joachim Barth

(A Salzburg Festival production, 2013)

Milan. 8th February 2017

The current production at La Scala of Verdi’s long (this performance was 5 hours 4 minutes) and celebrated Don Carlo is the revised 5 act 1887 Italian version. In most respects a magnificent opera, which superbly displays Verdi’s gift as a genuine musical dramatist. The subject matter, adapted from Schiller’s play, provided him with scope for strong characterisation and powerful situations and elicited some of his most memorable music. It is at the pinnacle of his production. Suffused with gravitas and pathos, its grandeur of conception and magnificence of staging ordains it the most complex and monumental of Verdi’s operas. Musical and dramatic intensity prevail in the many major issues confronted in the work – conflicts between private and public life, between father and son, church and state, despotism and liberalism, Catholic Spain and Protestant Flanders.

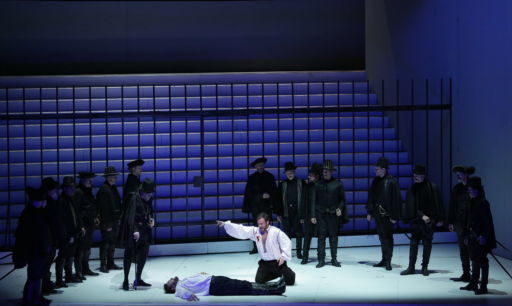

The colossal monochromatic white sets of Ferdinand Wögerbauer which soar up disappearing into the flies, give a sense of the enormous space and the monumental nature of each location, the breadth of history and the stature of its protagonists. Devoid of any decoration, only the most necessary large scale features are contoured… the enormous felled tree in the first act representing the forest at Fontainbleu, the arches of the St. Yuste cloister and the steps and barely sketched entrance to the convent in act two, the spartan cell-like room of Philip and the immense dungeon of act four. The enormous flight of stairs which descended from back stage towards bars of the prison cell front stage were used to great effect with the storming of the prison cell by the population. The simplicity of the sets put the protagonists and their emotional and psychological struggles in relief, regally detached from their surroundings.

The colossal monochromatic white sets of Ferdinand Wögerbauer which soar up disappearing into the flies, give a sense of the enormous space and the monumental nature of each location, the breadth of history and the stature of its protagonists. Devoid of any decoration, only the most necessary large scale features are contoured… the enormous felled tree in the first act representing the forest at Fontainbleu, the arches of the St. Yuste cloister and the steps and barely sketched entrance to the convent in act two, the spartan cell-like room of Philip and the immense dungeon of act four. The enormous flight of stairs which descended from back stage towards bars of the prison cell front stage were used to great effect with the storming of the prison cell by the population. The simplicity of the sets put the protagonists and their emotional and psychological struggles in relief, regally detached from their surroundings.

In turn, it also leaves a free hand and great scope to the lighting designer Joachim Barth to create all manner of atmosphere and effects, from the misty forest to the intense blue night scenes. Particularly effective was the realistic use of light and shade over the crowd scene which projected a sense of depth and movement. Beautifully crafted costumes by Anna Maria Heinreich. The crowd costumes were harmoniously similar but individually distinctive in design with varied hues of the same basic colours. The court was rigorously in black, as the real Philip ll commanded, but the royal figures were dressed in distinguished attire in luscious colours and fabrics, with the exception of Elizabeth’s rather out of place and out of character negligee in act four.

Peter Stein‘s direction was faithful to his well-known allegiance to the music, text and character. The portrayals were consistent and logical. The movements of the chorus natural and unassuming. His main characters acted with unaffectedness and spontaneity, unhindered by superfluous movement or action, allowing them a physical and psychological space to express the deepest layers of meaning hidden in the music. The irrepressible force of the opera driven by passions of power, love and vengeance was not encumbered by lengthy scene changes or complicated or distracting staging.

The portrayals were consistent and logical. The movements of the chorus natural and unassuming. His main characters acted with unaffectedness and spontaneity, unhindered by superfluous movement or action, allowing them a physical and psychological space to express the deepest layers of meaning hidden in the music. The irrepressible force of the opera driven by passions of power, love and vengeance was not encumbered by lengthy scene changes or complicated or distracting staging.

Taken individually, the cast sang beautifully but the overall impression was a distinct lack of vocal power to make their presence felt. Francesco Meli gave a magnetic performance as Don Carlo with his impeccable emission, even range, ringing upper register, sustained phrasing, nuanced colours and expressive interpretation. Kassimira Stoyanova gave a beautiful and heart-rending performance of her tender aria consoling her dismissed Lady in Waiting the Countess of Aremberg. Her beautifully honed voice was at its best in this lyric style, while in the more dramatic moments despite her incredible vocal commitment, the vocal line did not emerge and resulted light weight. Tastefully and intelligently, she did not force or resort to distorting her emission in order to overcome this problem. Ekaterina Semenchuk was a vocally determined and resolute Eboli especially in her final aria O Don Fatale. Simone Piazzola sang well but without any particular charisma in the role of Di Posa. The quality of Ferruccio Furlanetto‘s King Philip is untarnished. He gave an intimate introspective portrayal, laced with his deep, dark vocal quality, persuasive articulation and powerful declamation.  Mira Kares, as the Grand Inquisitor rose to the challenge in their dramatic scene together. Kares was a strong vocal and dramatic counterpart, completely convincing as the aged Inquisitor. Theresa Zitter was a breezy and spirited page Tebaldo, but the voice quality came across as thin and spindly. Fine singing and stage presence from the other roles; Martin Summer as the friar, Azer Zanda as Count Lerma and a herald, and Gustavo Castillo, Rocco Cavalluzzi , Dongho Kim, Victor Sporyshev, Chen Lingjie and Paolo Ingrasciotta as the Flemish deputies. A special mention for the splendid voice from heaven of Céline Mellon. Myung Whun Chung‘s musical direction brought out the rich and refined orchestral effects and the fluid and flexible forms. He kept the orchestra in line with the singers as far as volume, giving a much freer rein in the crowd scenes and auto-da-fé. Unexpectedly he was out of sync with the stage in a few occasions, the most notable being in the bass aria Dormirò Sol. The chorus of La Scala under the direction of Bruno Casoni was up to its usual high professional standard.

Mira Kares, as the Grand Inquisitor rose to the challenge in their dramatic scene together. Kares was a strong vocal and dramatic counterpart, completely convincing as the aged Inquisitor. Theresa Zitter was a breezy and spirited page Tebaldo, but the voice quality came across as thin and spindly. Fine singing and stage presence from the other roles; Martin Summer as the friar, Azer Zanda as Count Lerma and a herald, and Gustavo Castillo, Rocco Cavalluzzi , Dongho Kim, Victor Sporyshev, Chen Lingjie and Paolo Ingrasciotta as the Flemish deputies. A special mention for the splendid voice from heaven of Céline Mellon. Myung Whun Chung‘s musical direction brought out the rich and refined orchestral effects and the fluid and flexible forms. He kept the orchestra in line with the singers as far as volume, giving a much freer rein in the crowd scenes and auto-da-fé. Unexpectedly he was out of sync with the stage in a few occasions, the most notable being in the bass aria Dormirò Sol. The chorus of La Scala under the direction of Bruno Casoni was up to its usual high professional standard.