Metropolitan Opera, season 2017/2018

“PARSIFAL”

Opera in three acts.

Poem and music by Richard Wagner

Parsifal KLAUS FLORIAN VOGT

Kundry EVELYN HERLITZIUS (debut)

Gurnemanz RENÉ PAPE

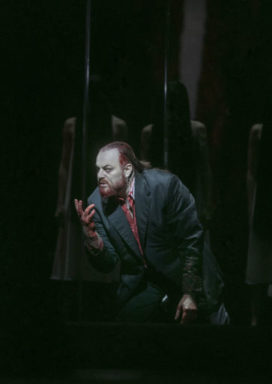

Amfortas PETER MATTEI

Klingsor EVGENY NIKITIN

Titurel ALFRED WALKER

Two Grail Knights MARK SCHOWALTER, RICHARD BERNSTEIN

Four Sentries KATHERINE WHYTE, SARAH LARSEN, SCOTT SCULLY, IAN KOZIARA

Six Flowermaidens HAERAN HONG, DEANNA BREIWICK, RENEE TATUM, DISELLA LARUSDOTTIR, KATHERINE WHYTE, AUGUSTA CASO

A Voice KAROLINA PILOU

Orchestra and Chorus of the Metropolitan Opera

Conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Chorus Master Donald Palumbo

Production François Girard

Set Designer Michael Levine

Costume Designer Thibault Vancraenenbroeck

Lighting Designer David Finn

Projection Designer Peter Flaherty

Choreographer Carolyn Choa

New York, 5th February 2018

In François Girard’s production of Parsifal, which triumphed when it first appeared at the Met in 2013 and joyously returned on Monday night, the wound of Amfortas which is draining the Grail-King, and the civilization to which he is central, of its life force and energy, has three visible manifestations. First, the king himself, played by a bearded, desperate Peter Mattei in a performance they will be talking about, and recalling with shining eyes, as long as opera endures; second in the pool of (possibly menstrual) blood in which Act II is set, and third as a brook or ravine (it widens into a ravine) that divides the stage in half in Acts I and III. This gash in the world separates women from men—no woman, not even the eldritch Kundry, dares cross to the men’s side, and the men remain firmly on theirs. Unstated in the libretto and the music, this division is a visual metaphor for a society in stasis. There can be no communication, no interaction, no reproduction here. The men in Act I follow traditions, waiting, bent over, in a seated circle for their king to do his ritual duty; the women (a crowd of them who do not sing, of course) listlessly observe them and shrug. The Grail exalts and nourishes the knights when the King goes through the invocatory motions, but this ever more agonizing trial is destroying him, and no one has more than momentary surcease to offer. Parsifal, reclaiming the wounding spear by defying the temptations of quick sex, returns to heal all the wounds: Kundry, whom he has baptized, upholds the Grail and, having healed Amfortas, Parsifal unites the two great symbolic props. Men and women cross the invisible boundary and mingle. Life continues. And in perhaps the most miraculous event of the entire shimmering evening, the Met audience did not begin to applaud until the music had reached its ultimate resolution.

In François Girard’s production of Parsifal, which triumphed when it first appeared at the Met in 2013 and joyously returned on Monday night, the wound of Amfortas which is draining the Grail-King, and the civilization to which he is central, of its life force and energy, has three visible manifestations. First, the king himself, played by a bearded, desperate Peter Mattei in a performance they will be talking about, and recalling with shining eyes, as long as opera endures; second in the pool of (possibly menstrual) blood in which Act II is set, and third as a brook or ravine (it widens into a ravine) that divides the stage in half in Acts I and III. This gash in the world separates women from men—no woman, not even the eldritch Kundry, dares cross to the men’s side, and the men remain firmly on theirs. Unstated in the libretto and the music, this division is a visual metaphor for a society in stasis. There can be no communication, no interaction, no reproduction here. The men in Act I follow traditions, waiting, bent over, in a seated circle for their king to do his ritual duty; the women (a crowd of them who do not sing, of course) listlessly observe them and shrug. The Grail exalts and nourishes the knights when the King goes through the invocatory motions, but this ever more agonizing trial is destroying him, and no one has more than momentary surcease to offer. Parsifal, reclaiming the wounding spear by defying the temptations of quick sex, returns to heal all the wounds: Kundry, whom he has baptized, upholds the Grail and, having healed Amfortas, Parsifal unites the two great symbolic props. Men and women cross the invisible boundary and mingle. Life continues. And in perhaps the most miraculous event of the entire shimmering evening, the Met audience did not begin to applaud until the music had reached its ultimate resolution.

No one who had seen the previous, superbly cast staging of Parsifal was surprised to find its grandeur  renewed on this occasion. The only uncertainty surrounded Yannick Nézet-Séguin, currently the company’s “Music Director Designate,” whatever that means. For a generation or two, James Levine’s magisterial beat held two productions of Parsifal on course; in 2013, with this one, we had the choice of Daniele Gatti or Asher Fisch. (I chose both.) At nearly five hours of music, Parsifal is an endurance test for everyone, and the conductor most prominently must keep the ever-returning, ever-renewing majesty of the score with its constant repetitions, its drawn-out dramatic structures ready to rise and fall and underline a complex melodrama with many symbols. Nézet-Séguin occasionally drifted but was never listless; one has heard this or that section explode more dynamically, bloom more ecstatically. But this was his first crack at the score; he’s got it down, he understands Wagner, and his command will improve. Let’s get that “Designate” off his title. This was my first exposure to the production from the orchestra level—previous visits had seen it from upstairs. Curiously, the downstairs patrons will not see the pool of red blood in Act II, only its reflections on the stony walls of Klingsor’s gorge and its steady spread through costumes and bedsheets. It is such a presence to upstairs viewers (impressed or disgusted as they may be), that this seemed a startling lacuna. The divisive gash in the earth in the other acts of Michael

renewed on this occasion. The only uncertainty surrounded Yannick Nézet-Séguin, currently the company’s “Music Director Designate,” whatever that means. For a generation or two, James Levine’s magisterial beat held two productions of Parsifal on course; in 2013, with this one, we had the choice of Daniele Gatti or Asher Fisch. (I chose both.) At nearly five hours of music, Parsifal is an endurance test for everyone, and the conductor most prominently must keep the ever-returning, ever-renewing majesty of the score with its constant repetitions, its drawn-out dramatic structures ready to rise and fall and underline a complex melodrama with many symbols. Nézet-Séguin occasionally drifted but was never listless; one has heard this or that section explode more dynamically, bloom more ecstatically. But this was his first crack at the score; he’s got it down, he understands Wagner, and his command will improve. Let’s get that “Designate” off his title. This was my first exposure to the production from the orchestra level—previous visits had seen it from upstairs. Curiously, the downstairs patrons will not see the pool of red blood in Act II, only its reflections on the stony walls of Klingsor’s gorge and its steady spread through costumes and bedsheets. It is such a presence to upstairs viewers (impressed or disgusted as they may be), that this seemed a startling lacuna. The divisive gash in the earth in the other acts of Michael  Levine’s set design is also less obvious from downstairs. Rather making up for this, Peter Flaherty’s extraordinary projections, constantly moving but somehow not intrusive (as the projections in, say, Robert LePage’s Ring were), are clearer downstairs: landscapes that mimic rolling limbs, turbulent lavalamp constructions, galaxies revolving and evolving.

Levine’s set design is also less obvious from downstairs. Rather making up for this, Peter Flaherty’s extraordinary projections, constantly moving but somehow not intrusive (as the projections in, say, Robert LePage’s Ring were), are clearer downstairs: landscapes that mimic rolling limbs, turbulent lavalamp constructions, galaxies revolving and evolving.

Returning for another crack at the score were, besides the glorious Mattei, whose anguished intensity sacrificed nothing in vocal beauty to give us the pain of the terrible wound, a pain as insatiable as lust, was René Pape’s all-but-tireless Gurnemanz, another of the fine Wagnerian portraits he has given us. Evgeny Nikitin’s burly Klingsor, another returning star, sang with dark authority and hissing malice. We first see him at curtain-rise in Act II, muttering unheard imprecations and making drastic gestures that evilly mimic and parody the hieratic gestures of Amfortas and his knights in Act I—just as Klingsor’s self-wounding magic diabolically parodies the Grail rite. Klaus Florian Vogt, who made his Met debut in 2006 as a spiritual, otherworldly Lohengrin, clearly of the same family as Parsifal (Lohengrin’s father). In the later work, his vapidity in the first  scenes seemed something on the Asberger’s scale, bewildered and uninvolved, and he remained passive and rather repelled during the Flower maiden scenes—but then, the spear-carrying, black-haired ladies in serried ranks who inhabit this production were hardly the flirtatious sort of Flower maiden. His cry of “Amfortas! Die Wünde!,” too, maintained his coolness, perhaps to excess—the accession of knowledge did not jolt his vocalism out of its serenity. One missed the tempered growl of Jonas Kaufmann in the role, but Vogt’s dazed, determined anguish was palpable when, shorn of his long locks, he reappeared in Act III. Evelyn Herlitzius made her Met debut as Kundry. A handsome woman and a fine, determined actress, she has a fruity but not ardent voice. The erotic, not to say maternal, phrases of Act II did not produce much sensual effect. Among the smaller roles, Alfred Walker was (though unseen) a standout as the moribund Titurel.Photo Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

scenes seemed something on the Asberger’s scale, bewildered and uninvolved, and he remained passive and rather repelled during the Flower maiden scenes—but then, the spear-carrying, black-haired ladies in serried ranks who inhabit this production were hardly the flirtatious sort of Flower maiden. His cry of “Amfortas! Die Wünde!,” too, maintained his coolness, perhaps to excess—the accession of knowledge did not jolt his vocalism out of its serenity. One missed the tempered growl of Jonas Kaufmann in the role, but Vogt’s dazed, determined anguish was palpable when, shorn of his long locks, he reappeared in Act III. Evelyn Herlitzius made her Met debut as Kundry. A handsome woman and a fine, determined actress, she has a fruity but not ardent voice. The erotic, not to say maternal, phrases of Act II did not produce much sensual effect. Among the smaller roles, Alfred Walker was (though unseen) a standout as the moribund Titurel.Photo Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera

New York, Metropolitan Opera: “Parsifal”