Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin, season 2017/2018

“TRISTAN UND ISOLDE”

Music drama in three acts.

Music and text by Richard Wagner after the romance “Tristan” by Gottfried von Straßburg.

Tristan VINCENT WOLFSTEINER

Isolde ANJA KAMPE

Brangäne EKATERINA GUBANOVA

Kurwenal BOAZ DANIEL

Marke, King of Cornwall STEPHEN MILLING

Melot STEPHAN RÜGAMER

A steersman ADAM KUTNY

A young sailor/a shepherd LINARD VRIELINK

Male singers of the Staatsopernchor

Staatskapelle Berlin

Conductor Daniel Baremboim

Chorus Raymond Hughes

Production and stage Dmitri Tcherniakov

Costumes Elena Zaytseva

Light Gleb Filshtinsky

Video Tieni Burkhalter

Berlin, 3rd March 2018

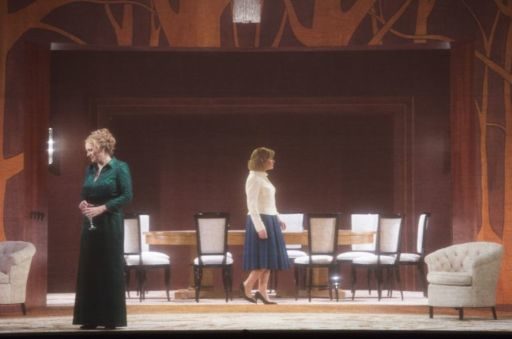

After the first few bars of the prelude there is no doubt that it is going to be a long Wagner night. Daniel Barenboim is a highly experienced conductor of Tristan und Isolde by Richard Wagner. His latest musical interpretation of the all-consuming, mystifying love story is above all time-consuming, which turns it into his loudest and slowest Tristan so far according to the saying “Wagner is as loud as long”. But like that he is able to present the Staatskapelle Berlin as a high-class orchestra. The composer’s harmonic language which ventures into bold, radical  chromaticism, came through in rich, full-bodied orchestral sound without neglecting the transparency to the contrapuntal lines that mingle continuously in the music. Only a greater sense of flow is missing sometimes. In that respect the orchestral performance is coherent while the production by Dmitri Tcherniakov does not unfold against a medieval tale of war between Cornwall and Ireland. The Russian director does not seem to believe in love, passion, desire, delight which he satirises in banal imagery. He has also designed the picture stage. The first act takes place in the classy lounge of a cruise-ship. The passengers are having a party and we can track the route of the ship on a flat screen including technical parameters or stock-market prices. The primed party guests, among them the young sailor, are leaving the lounge for Isolde and Brangäne to come in, dressed as business women (costumes by Elena Zaytseva). The deadly potion is in Isolde’s handbag and Brangäne switches the TV to a life cam on deck and Tristan appears on the screen. The stage is covered by a transparent curtain towards the auditorium that serves for black and white video projections by Tieni Burkhalter. In the first one Isolde gives Tristan a glass to drink before he really drinks the potion on stage which seems to be a modern party drug rather than a love potion making the two burst into hysterical laughter. The second act starts with a party again in a room from the 1950s. Tristan and Isolde (in a long green evening dress) are among the guests who soon take up their guns to go hunting. Happy to be alone after all, they behave like children. Physical love does not seem to be involved as Tristan rather turns into a teacher who starts to lecture on love. The second video projection during Brangäne’s “Habet acht!” shows Tristan with blood running down from his temple – funnily enough after all as Melot tries to strangle Tristan instead of wounding him with his sword at the end of the act. The third one is set in a moderately furnished room with green wallpaper and a cast-iron stove. We see another video projection with the photo of a couple with a boy, obviously Tristan as a child with his parents who really appear on stage later. It remains puzzling why, the more so as the mother is pregnant and according to the text, the father is already dead at that time. He died when he was fathering Tristan. The end is annoying: Tristan’s corpse is taken to a bed in a rear alcove while Isolde is singing the Liebestod. She finally closes the curtain of the alcove at the end and switches the light off. I cannot think of a more unromantic finale of Wagner’s masterpiece. The singers get somehow

chromaticism, came through in rich, full-bodied orchestral sound without neglecting the transparency to the contrapuntal lines that mingle continuously in the music. Only a greater sense of flow is missing sometimes. In that respect the orchestral performance is coherent while the production by Dmitri Tcherniakov does not unfold against a medieval tale of war between Cornwall and Ireland. The Russian director does not seem to believe in love, passion, desire, delight which he satirises in banal imagery. He has also designed the picture stage. The first act takes place in the classy lounge of a cruise-ship. The passengers are having a party and we can track the route of the ship on a flat screen including technical parameters or stock-market prices. The primed party guests, among them the young sailor, are leaving the lounge for Isolde and Brangäne to come in, dressed as business women (costumes by Elena Zaytseva). The deadly potion is in Isolde’s handbag and Brangäne switches the TV to a life cam on deck and Tristan appears on the screen. The stage is covered by a transparent curtain towards the auditorium that serves for black and white video projections by Tieni Burkhalter. In the first one Isolde gives Tristan a glass to drink before he really drinks the potion on stage which seems to be a modern party drug rather than a love potion making the two burst into hysterical laughter. The second act starts with a party again in a room from the 1950s. Tristan and Isolde (in a long green evening dress) are among the guests who soon take up their guns to go hunting. Happy to be alone after all, they behave like children. Physical love does not seem to be involved as Tristan rather turns into a teacher who starts to lecture on love. The second video projection during Brangäne’s “Habet acht!” shows Tristan with blood running down from his temple – funnily enough after all as Melot tries to strangle Tristan instead of wounding him with his sword at the end of the act. The third one is set in a moderately furnished room with green wallpaper and a cast-iron stove. We see another video projection with the photo of a couple with a boy, obviously Tristan as a child with his parents who really appear on stage later. It remains puzzling why, the more so as the mother is pregnant and according to the text, the father is already dead at that time. He died when he was fathering Tristan. The end is annoying: Tristan’s corpse is taken to a bed in a rear alcove while Isolde is singing the Liebestod. She finally closes the curtain of the alcove at the end and switches the light off. I cannot think of a more unromantic finale of Wagner’s masterpiece. The singers get somehow caught between the weird production and the climactic passages crested with sound by the orchestra. So they are covered by it or they have to force their voices apart from phrasing problems because of Barenboim’s slow conducting. I have seen the fifth performance after the première on 11th February. Andreas Schager had fallen ill with a flu so that Vincent Wolfsteiner had to replace him as Tristan at short notice. He has a powerful Charktertenor and manages the huge role with admirable stamina and impressive top notes. Isolde is sung by Anja Kampe who is not a genuine Hochdramatische. The medium range of her soprano sounds colourful and feminine particularly in lyrical moments. But she audibly has to make an effort as soon as it comes to dramatic outbreaks and the decisive climactic phrases. Top notes often fall out shrill and short. Her diction however is nearly impeccable. The rich-voiced mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Gubanova is an attractive Brangäne. Some deep notes are lacking lustre, top notes are vibrating. Altogether she sounds almost like a soprano so that her voice does not much differ from Isolde’s. Boaz Daniel has an imposing baritone. His Kurwenal sounds sturdy and powerful without any subtleties which do exist in the role, and his diction could be improved. Stephen Milling’s Marke is less angry than hurt and confused by Tristan’s betrayal. Vocally he is reliable but he does not really leave a mark. Stephan Rügamer is a convincing Melot. The cast is completed by Adam Kutny as a steersman and Linard Vrieling as a young sailor and shepherd. Photo Monika Rittershaus

caught between the weird production and the climactic passages crested with sound by the orchestra. So they are covered by it or they have to force their voices apart from phrasing problems because of Barenboim’s slow conducting. I have seen the fifth performance after the première on 11th February. Andreas Schager had fallen ill with a flu so that Vincent Wolfsteiner had to replace him as Tristan at short notice. He has a powerful Charktertenor and manages the huge role with admirable stamina and impressive top notes. Isolde is sung by Anja Kampe who is not a genuine Hochdramatische. The medium range of her soprano sounds colourful and feminine particularly in lyrical moments. But she audibly has to make an effort as soon as it comes to dramatic outbreaks and the decisive climactic phrases. Top notes often fall out shrill and short. Her diction however is nearly impeccable. The rich-voiced mezzo-soprano Ekaterina Gubanova is an attractive Brangäne. Some deep notes are lacking lustre, top notes are vibrating. Altogether she sounds almost like a soprano so that her voice does not much differ from Isolde’s. Boaz Daniel has an imposing baritone. His Kurwenal sounds sturdy and powerful without any subtleties which do exist in the role, and his diction could be improved. Stephen Milling’s Marke is less angry than hurt and confused by Tristan’s betrayal. Vocally he is reliable but he does not really leave a mark. Stephan Rügamer is a convincing Melot. The cast is completed by Adam Kutny as a steersman and Linard Vrieling as a young sailor and shepherd. Photo Monika Rittershaus

Nach den ersten Takten des Vorspiels ist zweifellos klar, dass es ein langer Wagnerabend wird. Daniel Barenboim ist ein äußerst erfahrener Dirigent von Richard Wagners Tristan und Isolde. Seine neueste musikalische Interpretation der alles verzehrenden, geheimnisvollen Liebesgeschichte ist vor allem zeitintensiv, was sie zu seinem lautesten und langsamsten Tristan bislang werden lässt nach dem Motto „Wagner ist so laut wie lang“. Auf diese Weise ist es ihm jedoch möglich, die Staatskapelle Berlin als erstklassiges Orchester herauszustellen. Die harmonische Sprache des Komponisten, die sich in kühne und radikale Chromatik vorwagt, setzt sich mit reichem sattem Orchesterklang durch ohne die Transparenz polyphoner Phrasen zu vernachlässigen, die konsequent in die Musik eingewoben sind. Es fehlt lediglich manchmal der  Sinn für mehr musikalischen Fluss. In dieser Hinsicht erweist sich die Orchesterleistung als stimmig, wohingegen die Inszenierung von Dmitri Tcherniakov die mittelalterliche Kriegsgeschichte zwischen Cornwall und Irland nicht stattfinden lässt. Der russische Regisseur scheint nicht an Liebe, Leidenschaft, Begehren, Wonne zu glauben, über die er sich in banalen Bildern eher lustig macht. Er hat auch die Guckkastenbühne ausgestattet. Der erste Akt spielt sich im edlen Salon eines Kreuzfahrtschiffes ab. Die Gäste feiern eine Party und wir können auf einem Flachbildschirm die Schiffroute verfolgen mit technischen Parametern oder Börsenkursen. Die angetrunkenen Partybesucher einschließlich des jungen Seemanns verlassen den Salon, damit Isolde und Brangäne als Geschäftsfrauen in Kostümen von Elena Zaytseva auftreten können. Der Todestrank befindet sich in Isoldes Handtasche und Brangäne schaltet den Bildschirm zu einer live-Kamera auf Deck um, wodurch Tristan ins Bild kommt. Ein durchsichtiger Gazevorhang trennt Bühne und Zuschauerraum und dient als Projektionsfläche für schwarz-weiß-Videos von Tieni Burkhalter. In der ersten Projektion gibt Isolde Tristan ein Glass zu trinken bevor er den Trank tatsächlich szenisch zu sich nimmt. Der scheint eher eine hippe Partydroge als ein Liebestrank zu sein, worauf beide einen hysterischen

Sinn für mehr musikalischen Fluss. In dieser Hinsicht erweist sich die Orchesterleistung als stimmig, wohingegen die Inszenierung von Dmitri Tcherniakov die mittelalterliche Kriegsgeschichte zwischen Cornwall und Irland nicht stattfinden lässt. Der russische Regisseur scheint nicht an Liebe, Leidenschaft, Begehren, Wonne zu glauben, über die er sich in banalen Bildern eher lustig macht. Er hat auch die Guckkastenbühne ausgestattet. Der erste Akt spielt sich im edlen Salon eines Kreuzfahrtschiffes ab. Die Gäste feiern eine Party und wir können auf einem Flachbildschirm die Schiffroute verfolgen mit technischen Parametern oder Börsenkursen. Die angetrunkenen Partybesucher einschließlich des jungen Seemanns verlassen den Salon, damit Isolde und Brangäne als Geschäftsfrauen in Kostümen von Elena Zaytseva auftreten können. Der Todestrank befindet sich in Isoldes Handtasche und Brangäne schaltet den Bildschirm zu einer live-Kamera auf Deck um, wodurch Tristan ins Bild kommt. Ein durchsichtiger Gazevorhang trennt Bühne und Zuschauerraum und dient als Projektionsfläche für schwarz-weiß-Videos von Tieni Burkhalter. In der ersten Projektion gibt Isolde Tristan ein Glass zu trinken bevor er den Trank tatsächlich szenisch zu sich nimmt. Der scheint eher eine hippe Partydroge als ein Liebestrank zu sein, worauf beide einen hysterischen Lachanfall bekommen. Der zweite Akt beginnt wieder mit einer Party, diesmal in einem Raum aus den 1950ern. Tristan und Isolde (in einem langen grünen Abendkleid) sind unter den Gästen, die bald ihre Gewehre nehmen, um auf Jagd zu gehen. Glücklich, endlich allein zu sein, benehmen sie sich wie Kinder. Körperliche Liebe scheint keine Rolle zu spielen, da Tristan eher zum Lehrer mutiert, der eine Lektion in puncto Liebe erteilt. Die zweite Videoprojektion während Brangänes Wachgesangs zeigt Tristan mit Blut, das von seiner Schläfe herunterläuft – schließlich merkwürdig, da Melot am Ende des Aktes versucht, Tristan zu erwürgen anstatt ihn mit seinem Schwert zu verwunden. Der dritte Akt spielt in einem bescheiden eingerichteten Zimmer mit grüner Tapete und gusseisernem Ofen. Wir sehen wieder eine Videoprojektion mit dem Foto eines Paares mit einem Jungen, offensichtlich Tristan als Kind mit seinen Eltern, die tatsächlich später auftreten. Es bleibt ein Rätsel warum, zumal die Mutter schwanger ist und aus dem Text hervorgeht, dass der Vater da schon tot war. Er starb bei Tristans Zeugung. Das Ende ist ärgerlich: Tristans Leiche wird auf ein Bett in einem hinteren Alkoven gebracht während Isolde den Liebestod singt. Am Ende zieht sie den Vorhang zum Alkoven zu und macht das Licht aus. Ich kann mir kein unromantischeres Finale von Wagners Meisterwerk vorstellen! Die Sänger bleiben irgendwie zwischen der merkwürdigen Inszenierung und den vom Orchester mit Klang gefluteten Schlüsselstellen stecken. Ergo werden sie von ihm zugedeckt oder gezwungen zu forcieren, abgesehen von Phrasierungsproblemen wegen Barenboims langsamer Tempi. Ich habe die fünfte Vorstellung nach der Premiere am 11. Februar gesehen. Andreas Schager war an einer Grippe

Lachanfall bekommen. Der zweite Akt beginnt wieder mit einer Party, diesmal in einem Raum aus den 1950ern. Tristan und Isolde (in einem langen grünen Abendkleid) sind unter den Gästen, die bald ihre Gewehre nehmen, um auf Jagd zu gehen. Glücklich, endlich allein zu sein, benehmen sie sich wie Kinder. Körperliche Liebe scheint keine Rolle zu spielen, da Tristan eher zum Lehrer mutiert, der eine Lektion in puncto Liebe erteilt. Die zweite Videoprojektion während Brangänes Wachgesangs zeigt Tristan mit Blut, das von seiner Schläfe herunterläuft – schließlich merkwürdig, da Melot am Ende des Aktes versucht, Tristan zu erwürgen anstatt ihn mit seinem Schwert zu verwunden. Der dritte Akt spielt in einem bescheiden eingerichteten Zimmer mit grüner Tapete und gusseisernem Ofen. Wir sehen wieder eine Videoprojektion mit dem Foto eines Paares mit einem Jungen, offensichtlich Tristan als Kind mit seinen Eltern, die tatsächlich später auftreten. Es bleibt ein Rätsel warum, zumal die Mutter schwanger ist und aus dem Text hervorgeht, dass der Vater da schon tot war. Er starb bei Tristans Zeugung. Das Ende ist ärgerlich: Tristans Leiche wird auf ein Bett in einem hinteren Alkoven gebracht während Isolde den Liebestod singt. Am Ende zieht sie den Vorhang zum Alkoven zu und macht das Licht aus. Ich kann mir kein unromantischeres Finale von Wagners Meisterwerk vorstellen! Die Sänger bleiben irgendwie zwischen der merkwürdigen Inszenierung und den vom Orchester mit Klang gefluteten Schlüsselstellen stecken. Ergo werden sie von ihm zugedeckt oder gezwungen zu forcieren, abgesehen von Phrasierungsproblemen wegen Barenboims langsamer Tempi. Ich habe die fünfte Vorstellung nach der Premiere am 11. Februar gesehen. Andreas Schager war an einer Grippe  erkrankt, so dass Vincent Wolfsteiner für ihn kurzfristig als Tristan einspringen musste. Er besitzt einen kraftvollen Charktertenor und bewältigt die Riesenrolle mit bemerkenswertem Durchhaltevermögen und beeindruckenden Spitzentönen. Isolde wird von Anja Kampe gesungen, die keine echte Hochdramatische ist. Die Mittellage ihres Soprans klingt farbenreich und weiblich besonders in lyrischen Passagen. Jedoch muss sie sich hörbar anstrengen bei dramatischen Ausbrüchen und den entscheidenden Höhepunkten. Spitzentöne geraten oft grell und kurz. Ihre Diktion ist dagegen nahezu tadellos. Die großstimmige Mezzosopranistin Ekaterina Gubanova gibt eine attraktive Brangäne. Einigen tiefen Tönen fehlt der Glanz während die Höhe zum Vibrato neigt. Insgesamt klingt sie fast wie ein Sopran, so dass sich ihre Stimme kaum von Isoldes unterscheidet. Boaz Daniel hat einen beeindruckenden Bariton. Sein Kurwenal klingt robust und kraftvoll ohne die Feinheiten, die es tatsächlich in der Partie gibt, und seine Diktion ist verbesserungswürdig. Stephen Millings Marke ist weniger wütend als verletzt und verwirrt durch Tristans Verrat. Er ist stimmlich zuverlässig, aber hinterlässt keinen bleibenden Eindruck. Stephan Rügamer ist ein überzeugender Melot. Adam Kutny als Steuermann und Linard Vrieling als junger Steuermann und Hirt vervollständigen die Besetzung. Photo Monika Rittershaus

erkrankt, so dass Vincent Wolfsteiner für ihn kurzfristig als Tristan einspringen musste. Er besitzt einen kraftvollen Charktertenor und bewältigt die Riesenrolle mit bemerkenswertem Durchhaltevermögen und beeindruckenden Spitzentönen. Isolde wird von Anja Kampe gesungen, die keine echte Hochdramatische ist. Die Mittellage ihres Soprans klingt farbenreich und weiblich besonders in lyrischen Passagen. Jedoch muss sie sich hörbar anstrengen bei dramatischen Ausbrüchen und den entscheidenden Höhepunkten. Spitzentöne geraten oft grell und kurz. Ihre Diktion ist dagegen nahezu tadellos. Die großstimmige Mezzosopranistin Ekaterina Gubanova gibt eine attraktive Brangäne. Einigen tiefen Tönen fehlt der Glanz während die Höhe zum Vibrato neigt. Insgesamt klingt sie fast wie ein Sopran, so dass sich ihre Stimme kaum von Isoldes unterscheidet. Boaz Daniel hat einen beeindruckenden Bariton. Sein Kurwenal klingt robust und kraftvoll ohne die Feinheiten, die es tatsächlich in der Partie gibt, und seine Diktion ist verbesserungswürdig. Stephen Millings Marke ist weniger wütend als verletzt und verwirrt durch Tristans Verrat. Er ist stimmlich zuverlässig, aber hinterlässt keinen bleibenden Eindruck. Stephan Rügamer ist ein überzeugender Melot. Adam Kutny als Steuermann und Linard Vrieling als junger Steuermann und Hirt vervollständigen die Besetzung. Photo Monika Rittershaus